For many Ghanaians living with diabetes, the simple act of checking blood sugar has become a costly privilege, forcing them to live with uncertainty and risk every day.

A glucometer costs between One Hundred and Fifty Ghana Cedis to Two Hundred and Fifty Ghana Cedis depending on the brand and where you buy it. The strips, which come in packs of 50, can set you back Eighty to One Hundred and Twenty Ghana cedis, also depending on the brand and location.

At a small pharmacy in Sunyani in the Bono Region, sixty-year-old Madam Alice Nyarko stands quietly at the counter, clutching her worn purse. Her hands shake slightly as she asks for a pack of glucose test strips. When the attendant tells her the price, one hundred and twenty cedis, she takes a deep breath, closes her purse, and forces a faint smile. “I’ll come back next week,” she says softly, though she knows she will not.

Alice has lived with diabetes for eight years. She no longer checks her blood sugar every day. Instead, she waits until her body sends her warning signs. “Sometimes I just know when it’s high,” she said. “My body will be shaking. Then I drink water and lie down.” For her, and many others, the cost of a simple finger prick has become too much to bear.

The Ghana Health Service estimates that more than 800,000 Ghanaians are living with diabetes, while many more remain undiagnosed. Medication is partly covered under the National Health Insurance Scheme, but testing supplies are not. Patients must buy their own glucose meters, test strips, and lancets. These can cost up Five Hundred Ghana Cedis a month for those who monitor regularly. In a country where many earn less than that, daily testing is beyond reach.

Nurse Lydia Tenkorang, who runs a diabetes clinic in Techiman in the Bono East Region, witnesses this struggle every day. “Without test strips, patients can’t manage their condition properly,” she said. “They depend on how they feel, but that is not reliable.” She recalled a patient who arrived at her clinic unconscious. His sugar level was so low that the glucometer could not give a reading. He had been taking insulin without checking because he could not afford the strips. “He nearly died trying to help himself,” she said.

An AI generated photograph of a couple taking a peaceful evening walk after dinner for better health.

Across Ghana, pharmacists and nurses share similar stories. The testing devices are imported, and as the value of the cedi falls, prices rise. Even public hospitals find it hard to restock testing kits for community screenings. At Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, doctors can test patients during visits, but home monitoring remains a major gap, leading to frequent hospital admissions.

A report by the International Diabetes Federation shows that more than 70 percent of Ghanaians with diabetes do not check their blood sugar regularly, mainly because of the cost. Without proper monitoring, doctors have little data to guide treatment, and patients are left to guess their next step.

A banker in Accra feeling dizzy at work, unaware it’s an early sign of diabetes.

For Kwabena Mensah, a taxi driver in Kumasi in the Ashanti region, this uncertainty is part of daily life. “My medicine alone costs about two hundred cedis,” he said. “If I buy strips too, I can’t feed my family. So I just hope to feel strong each day.”

The financial strain is only part of the problem. Many patients live with constant worry and frustration for not being able to manage their condition properly. Doctors warn that poor monitoring leads to serious complications that are much more expensive to treat. Dialysis for kidney failure can cost over a thousand Ghana Cedis per session, while blindness and amputation are permanent. “We spend more trying to fix emergencies instead of preventing them,” said Dr Afua Agyeman of Korle Bu Teaching Hospital. “A pack of strips may seem costly, but it is cheaper than a hospital bed.”

A young couple enjoying sugary meals and drinks during a cozy evening date

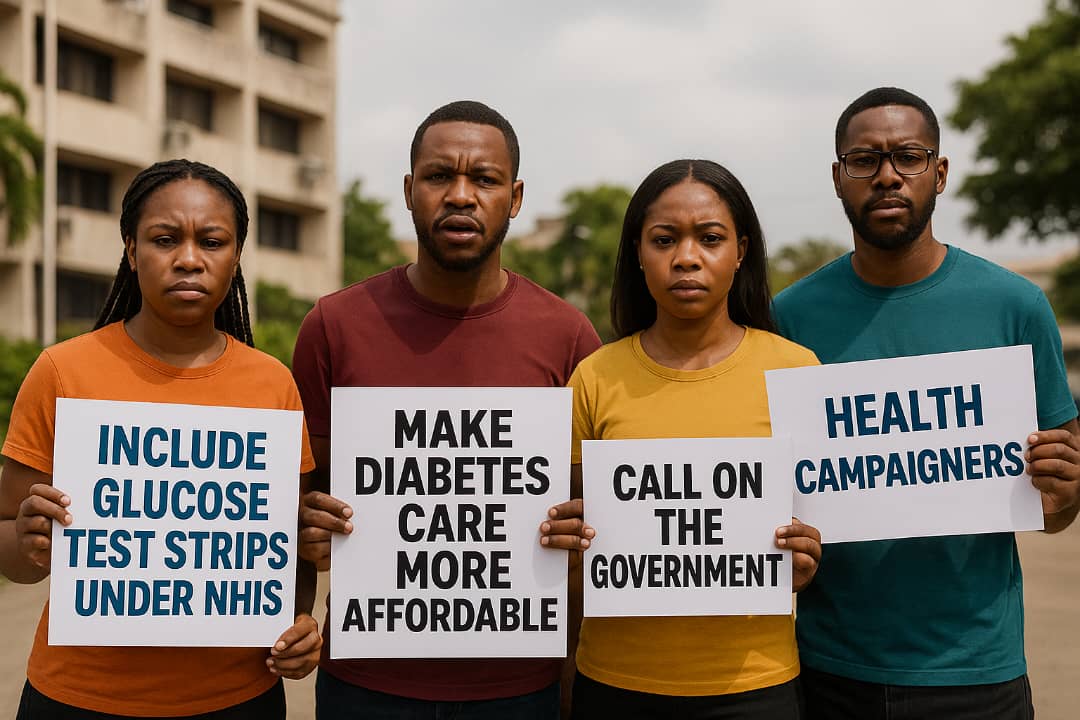

Health campaigners have been calling for test kits to be subsidised or included under the national insurance scheme. Some non-governmental organisations donate free meters to hospitals, but supplies are limited. “People should not have to choose between testing their sugar and eating supper,” Dr Agyeman said.

A diabetes patient unable to afford a pack of glucose test strips.

In her small home, Madam Alice Nyarko still keeps her old glucose meter on a wooden shelf. It still works, but she rarely uses it. “I test when I get some money or when I feel too weak,” she said quietly. “Sometimes I wish I could check every morning like the nurse told me, but life makes it hard.”

Health campaigners calling on the government to include glucose test strips under the National Health Insurance Scheme to make diabetes care more affordable.

Her story represents thousands of others across the country. Ordinary people are trying to live with a disease that demands precision in a system that offers little support. Every untested day brings risk, and every skipped check is a prompt of how costly survival has become.

The finger prick that should protect them now feels like a privilege. Until testing becomes affordable, Ghana’s fight against diabetes will remain an uphill journey for those who can least afford to lose.

By: Nana Ama Asantewaa Kwarko

Email: N.kwarko@yahoo.com