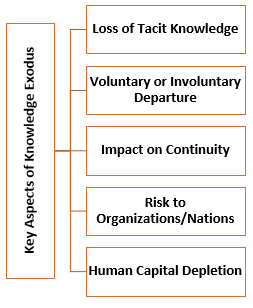

“Knowledge exodus” is a term used to describe the loss of critical knowledge, expertise, and intellectual capital from an organization, industry, or nation, usually due to a mass departure or retirement of experienced personnel.

It’s essentially a form of brain drain on a localized, internal, or focused scale where the departing individuals take with them the valuable, often undocumented, tacit knowledge they’ve accumulated over years of experience.

The most significant aspect to knowledge exodus is the loss of tacit knowledge—the know-how, best practices, problem-solving skills, and deep contextual understanding that is hard to codify or write down.

This ‘exodus’ can be driven by high retirement rates (the “silver tsunami”), high turnover, major layoffs, or shifts in employment trends like the “Great Resignation” (as seen in recent years).

In short, it’s the emptying out of an organization’s collective institutional memory and expertise, which is its most valuable, unique, and non-renewable resource.

Regardless, knowledge exodus can severely disrupt business continuity and the efficiency of critical processes because the knowledge necessary to run operations smoothly is no longer readily available within the remaining workforce.

This phenomenon poses a strategic risk, leading to reduced innovation, higher operational errors, decreased service quality, damaged organizational knowledge flows, and difficulty in training replacements. On a larger scale, particularly if it involves an entire industry or country, it represents the depletion of national or sectoral human capital, which can hinder economic growth and competitiveness.

Nonetheless, the phenomenon appears to cripple into our various communities of Ghana. The constant exodus of youth and skilled individuals from rural communities in Ghana’s Volta Region, for example, to urban centres and abroad represents a severe form of “knowledge exodus.”

This departure, fueled by a corrosive mix of psychosocial and economic pressures, starves the towns of the very human capital needed for development. The critical issue is the failure of these migrants to return with their new knowledge, preventing the virtuous cycle of learning and reinvestment.

The absence of basic infrastructure; poor education and healthcare, unreliable power, and inadequate roads signal that the community does not value its citizens’ welfare or their potential to establish businesses.

Likewise, the absence of local financial institutions, entrepreneurial mentorship, and a robust local market inhibits any efforts by returnees to establish enterprises, leading to failure and discouragement.

Rural economies are often stagnant, relying on subsistence agriculture. The lack of diversified jobs, coupled with a significant wage gap compared to urban centres, makes migration an inevitable economic survival strategy.

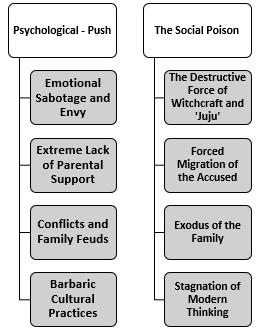

However, the primary drivers of this community knowledge exodus can be grouped into two interconnected categories that push people out, making a return unpalatable or impossible; the psychological push and the social poison.

Emotional and social issues—hatred, sabotage, and extreme lack of parental support—are profound factors that act as a powerful “push” factor for rural-to-urban migration, often undermining economic initiatives more than a lack of resources alone.

The traditional extended family structure, while historically a safety net, is increasingly becoming a source of intense conflict, particularly in the context of economic strain and social change.

These issues create a toxic social environment that cripples individual ambition and collective development.

In many African cultures, individual success can be perceived as coming at the expense of others, especially within the extended family or community. When a young person tries to start a business or excel, they become a target for jealousy and resentment. This resentment often manifests as “psychological and emotional sabotage”—gossip, unfounded accusations (sometimes of witchcraft/juju), or malicious obstruction of their plans.

A young, ambitious person will conclude that success is impossible to sustain at home and is forced to migrate to the city where they can operate with a greater degree of anonymity and independence from family scrutiny.

Witchcraft accusations are a form of social violence that contributes significantly to the population exodus. An extremely critical, yet often unaddressed, factor in rural development is the beliefs and resulting accusations of witchcraft and ‘juju’ (black magic/ritualism) do not just create social conflict; they actively dismantle the foundations of a modern, productive economy.

Individuals, typically older women, widows, or the socially weak, who are accused of witchcraft following an illness or death, are often violently expelled from their communities and banished to ‘witch camps’ or forced to flee. This banishment is a gross human rights violation and removes a segment of the population that holds valuable traditional knowledge, caregiving roles, and moral guidance.

The immediate and extended family members of the accused, or those who defend them, also face social exclusion, threats, and fear for their lives. These productive, working-age family units are forced to relocate to the cities, further exacerbating the rural brain drain and loss of essential family labour.

The constant tendency to attribute all misfortune (illness, business failure, crop blight) to witchcraft or ‘juju’ actively discourages the application of modern, scientific, or logical solutions.

The community is perpetually trapped in a cycle where problems are solved by diviners and traditional priests rather than by investing in education, pest control, modern medicine, or business analysis.

Also, barbaric cultural practices that limit freedom, suppress innovation, or marginalise certain groups (e.g., gender inequality, harmful widowhood rites) are often viewed by the youth as backward and a direct barrier to a modern, productive life.

Witchcraft and ‘juju’ are the destructive force and a social poison, driving out the vulnerable and the educated.

In addition, extreme lack of parental support, and the shift from traditional communal-styleparenting to modern nuclear family demands, combined with economic stress, can leave ambitious youth feeling abandoned. They may not receive the necessary emotional capital (encouragement, belief) or instrumental capital (initial seed money, access to land/resources) from their parents.

This pushes the youth toward high-risk, unguided migration to urban centers, viewing a lack of family support as a sign that their future must be found elsewhere. This may also drive conflicts and family Feuds, and persistent, unresolved disputes over land, chieftaincy, or inheritance create a toxic atmosphere of distrust and division. This paralyses communal efforts and makes local investment risky and stressful.

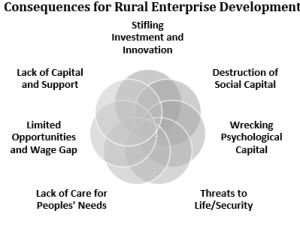

Consequences for Rural Enterprise Development

In effect, these are hindering rural enterprise development. A thriving local economy requires collaboration and emotional resilience, both of which are destroyed by family conflict.

Enterprise often relies on trust and cohesive teamwork (social capital). When there is “hatred for one another” and constant “turf wars” within the family unit, it becomes impossible to form reliable, long-term business partnerships or cooperatives. The entrepreneur faces internal conflict that absorbs time, money, and mental energy better spent on the business.

Entrepreneurial success requires a strong psychological foundation: self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism. Constant emotional battering, hate speech, and sabotage from core family members directly erodes this psychological capital, leading to stress, depression, and a higher propensity to abandon the venture at the first sign of difficulty. Studies show that family support is a crucial protective factor against entrepreneurial stress; its absence makes failure more likely. When community conflicts escalate into violence, or local justice systems are perceived as ineffective or biased, the educated and entrepreneurial are often the first to leave for the security of the city.

The impact of witchcraft and ‘juju’ on rural enterprise and productivity can be either economic freeze and/or the social poison. The prevalence of these beliefs creates a pervasive atmosphere of fear that directly discourages the very behaviour needed for economic growth.

- Fear of Success and the “Witch Tax”; in rural communities, success, wealth, or innovation is often viewed with suspicion. A person who quickly prospers—especially a returning migrant who opens a new business—is immediately seen as having used ‘juju’ or ‘black magic’ to gain an unfair advantage, or is perceived as a target for a jealous relative’s witchcraft. This fear encourages a culture of deliberate underperformance and non-investment. Why invest savings to build a house or start a large farm only to be accused, extorted, or have your progress “spoiled” by a jealous kin? The most innovative simply choose to keep their capital and skills in the city or abroad.

- Erosion of Social Capital and Trust; enterprise development relies on people forming partnerships, cooperatives, and credit groups. When a community lives in fear that a partner’s crop failure is due to ‘juju’ or that a business associate is a witch who will sabotage the venture, trust collapses. This spiritual insecurity prevents the formation of formal or informal business relationships, limiting ventures to basic, non-scalable family-only operations.

- Ritualism as a ‘Business Strategy’; the belief in ‘juju’ often leads some individuals to seek quick, illicit wealth through ritual means (e.g., ritual murders, stealing human body parts for ‘magic’). This is particularly prevalent among frustrated, unemployed youth. This criminal and barbaric pursuit not only endangers the lives of the most vulnerable (children and the elderly) but also further deteriorates the moral fabric and security of the community, driving out law-abiding, productive citizens.

Possible Remedies

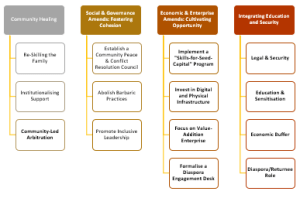

In view of damming effects of hindering rural enterprise development, there is urgent need to make amends in our communities. To harness the knowledge and experience of the diaspora, communities must actively cultivate an environment that is both socially cohesive and economically viable.

First, strategies for amends need to focus community healing. Addressing these deep-seated emotional and interpersonal issues requires interventions focused on the family unit as the primary economic and social institution.

There is urgent need for Re-Skilling the Family. This involves shifting the family’s mindset from a model of rivalry to one of collective benefit. Ghana needs to embark on Entrepreneurial Family Education, and offer workshops that target the entire family (parents, youth, and elders), not just the potential entrepreneur. The curriculum should focus on:

§ Role of the Family as a “Board of Directors”: Teach family members how to support a relative’s venture through non-financial means (e.g., providing emotional support, marketing, and guarding the premises) and highlight the collective benefit (money for school fees, better housing) that accrues from the individual’s success.

- Establish Mutual Support/Credit Unions: Encourage the formation of formally registered community and savings groups (VSLAs/Co-ops) that are governed by legal bylaws and transparency. Provides a collective safety net and a framework of objective rules to manage credit and investment, bypassing the mistrust inherent in the ‘witchcraft’ mindset.

§ Conflict Resolution & Communication: Provide training in non-violent communication to address jealousy and suspicion before they escalate into open sabotage or accusations.

- Strictly Enforce the Anti-Witchcraft Law: The government must ensure that police and the judiciary in our Districts actively and consistently investigate and prosecute all accusations, banishments, and acts of violence related to witchcraft. Establishes the rule of law, making the community a secure place to invest and live without fear of arbitrary social violence.

§ Promote Transparency as Trust: Encourage successful family members in the city to openly and honestly share their income source and investment plans with their immediate family, which helps demystify wealth and counter the assumption that success is based on ‘juju’ or ill-gotten gains.

Returnees who succeed in business must publicly and vocally attribute their success to hard work, smart planning, and education, not ‘juju’. Their public conduct should model transparency and modern business ethics, and undermines the “witchcraft-as-explanation” narrative by providing a tangible, visible, and modern alternative for achieving wealth.

§ Targeted Public Health Education: Launch campaigns that explain the scientific causes of common ailments, old-age conditions (like dementia), and crop diseases. Partner with community radio and religious leaders to demystify misfortune. Replaces superstitious explanations with rational, scientific solutions, fostering a mindset open to modern farming, medicine, and business techniques.

We must intentionally target the skills and capital of the diaspora, creating pull factors for their return and investment. We need to create a structured initiative where returnee professionals (mechanics, nurses, IT specialists, teachers) who commit to a one-year service in the community are provided with seed funding or access to micro-credit to establish their own enterprise afterward.

This directly translates their urban/international knowledge into local business. The District Assembly or a community body should establish a point of contact dedicated to facilitating diaspora investment. This desk would provide information on local investment opportunities, streamline administrative processes, and help secure land free from the feuds mentioned above.

We also need to begin Institutionalizing Support in the following ways:

- Mentorship and Peer Networks: Establish formal, safe, and confidential mentorship programs where young entrepreneurs can be paired with successful, non-family community elders or business owners who can provide emotional and strategic support outside the toxic family environment.

- Apprenticeship and Co-Learning: Formalize apprenticeships in traditional trades, local governance, or indigenous ecological knowledge. These long-term, hands-on relationships create strong social bonds and ensure the seamless transfer of complex, unwritten (tacit) knowledge.

- Community of Practice (CoP) Groups: Create small, voluntary groups focused on a specific skill (e.g., traditional weaving, carpentry, local conflict resolution). These horizontal networks promote peer-to-peer learning and sustain the knowledge beyond a single teacher-student relationship, thereby strengthening bonding social capital.

- Reverse Mentoring Programs: Establish structured programs where elders teach traditional, tacit knowledge (e.g., sustainable farming, herbal medicine, traditional crafts, local history) to the youth, while the youth teach elders modern, explicit knowledge (e.g., digital literacy, social media for marketing, mobile money systems). This dual exchange creates mutual utility and respect.

These intergenerational knowledge transfer mechanisms represent the most effective way to retain knowledge and build cohesion is by making the young dependent on the old for critical, valuable information.

Community-Led Arbitration: Train local traditional authorities and respected leaders to act as official, neutral arbitrators in family disputes over land, finances, or accusations of sabotage that are impacting a productive enterprise. This gives the entrepreneur a non-violent, official recourse against internal family malice.

The core challenge here is to establish trust and a functioning local governance system that resolves disputes transparently. There is need to empower respected elders, women leaders, and returning professionals (lawyers, retired civil servants) to mediate land and family disputes using a blend of modern law and reformed customary practice. Focus on “Win-Win” collaboration rather than punitive measures to heal rifts.

Community leaders and the District Assembly must publicly identify and abolish cultural practices that violate human rights or deter social progress. Leverage the influence of diaspora members to champion these reforms, giving the community a modern, progressive image.

In addition, there is need to ensure that community development committees are not monopolized by a few families but include youth, women, and diaspora representatives in decision-making. This guarantees that projects and policies reflect the needs of all segments of the population.

Ensuring social cohesion by retaining knowledge capital primarily involves deliberately engineering interaction and transfer between generations and groups, effectively turning knowledge-sharing into a continuous community-building exercise. Knowledge capital retention strengthens cohesion by creating shared value, mutual respect, and a collective sense of identity.

We must embark on Digital Preservation and Archiving; leveraging modern technology to document and manage local knowledge makes it accessible, valuable, and protected for future generations. These strategies integrate formal preservation with social engagement. There is the need to do the following:

- Indigenous Knowledge Digital Libraries: Develop digital repositories, managed by the community, to document oral histories, local agricultural practices, traditional recipes, and medicinal knowledge using text, audio, and video formats. This prevents loss due to out-migration and provides a secure, organized record.

- Digital Storytelling: Train youth to use simple technology (smartphones) to interview elders and create short documentary-style videos about their skills and life experiences. Sharing these narratives online or in community centers not only preserves the knowledge but also raises the status and value of the elders within the community.

- Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Mapping: Collaborate with universities or NGOs to map local resources, sacred sites, and traditional land-use boundaries based on the knowledge of elders. This integration of local knowledge with modern technology provides practical, defendable utility for community planning and resource management.

For knowledge to be truly retained, it must be validated and utilized in the community’s decision-making process. We must begin Integrating Knowledge into Local Governance and Education. This also requires the following:

- Curriculum Integration: Work with local schools to integrate local history, traditional ethical values, and indigenous ecological knowledge into the formal or non-formal curriculum. This institutionalizes the knowledge and reinforces cultural identity for children.

- Local Policy Committees: Establish formal roles for respected knowledge-holders (elders, master craftspersons) on local development or land-use planning committees. This ensures that traditional, time-tested wisdom is applied to modern challenges, thereby legitimizing the knowledge and its holders.

- Knowledge-Based Community Events: Host regular cultural festivals, storytelling competitions, or local trade fairs where the focus is explicitly on the demonstration and celebration of local knowledge and skills. This creates a positive feedback loop, linking the retention of knowledge directly to pride and social recognition.

Overall, there is the need to prioritize the provision of reliable internet access and basic amenities (e.g., boreholes, health posts). Modern enterprises, from agritech to virtual assistant services, require connectivity to thrive. Good roads reduce the cost of doing business.

The key to reversing this trend and fostering rural enterprise is to transform the community from a place of departure into a place of opportunity and belonging.

Nevertheless, instead of just exporting raw materials (e.g., yams, cassava), establish small-scale processing units (e.g., gari processing plants, fruit drying, textile production) run as communal or private ventures. These enterprises create higher-paying jobs and are naturally attractive to returnees with technical or managerial skills.

Addressing this deep-seated issue requires a multi-faceted approach that integrates law, education, and economic reform. By addressing the social rot and economic neglect head-on, rural communities in Ghana can transition from being net exporters of talent to becoming hubs of localized enterprise and productivity, finally capitalizing on the wealth of knowledge their migrating sons and daughters have acquired.

By criminalizing the violence, educating the populace, and replacing spiritual insecurity with economic opportunity, the rural Ghana can finally break the cycle of fear that is driving away its most valuable asset: its own people.

Constance is a Risk & Enterprise Development Expert