For many Ghanaians, the Ghana cedi is more than just money, it’s a symbol of national pride, independence, and self-determination.

From the marketplace to the boardroom, the cedi is central to Ghanaian life, used for buying goods, paying workers, saving for the future, and planning family budgets.

Ghana’s currency has undergone a remarkable transformation from the use of cowries and the British pound to the introduction of the cedi in 1965.

The cedi, in many ways, came in as the heartbeat of a young nation charting its own course, but sixty years on, that promise feels tested.

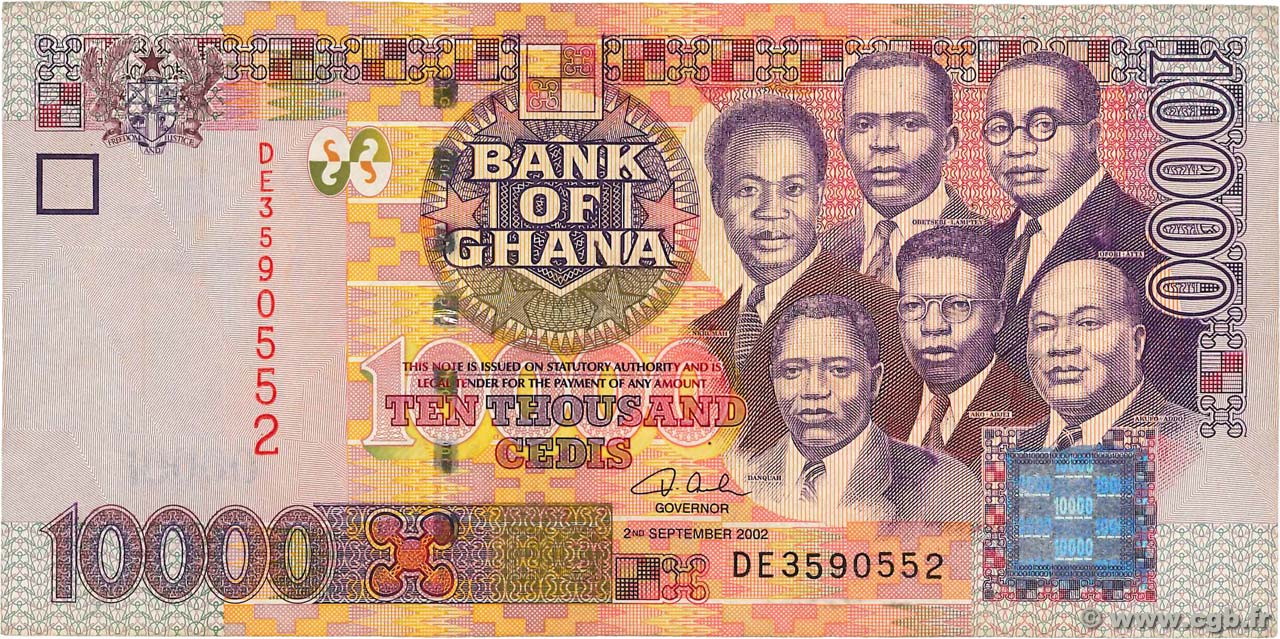

Redenomination of the Cedi

In 2007, there was a redenomination, slashing four zeros from the currency, turning ¢10,000 into GH¢1, with the popular slogan, “the value is the same”.

While it simplified accounting and transactions, inflation over the years has severely reduced the cedi’s purchasing power.

For instance, the GH¢2 note, once equivalent to ¢20,000, now holds far less value in everyday use.

Printing the Cedi

Despite being Ghana’s official currency, the cedi is still printed abroad by firms like De La Rue in the UK, costing the Bank of Ghana GH¢337.5 million in 2020 alone.

The country lacks a local mint, and printing costs continue to rise.

This has led the Central Bank to consistently urge the public to handle currency notes responsibly, to minimise waste and protect the value of the cedi.

Cedi’s comeback – but does it hold?

Over the decades, the currency’s strength and credibility have come under growing pressure.

Inflation, chronic depreciation, and the creeping dominance of the US dollar have shaken the public’s trust in what used to be a strong national symbol.

But according to the Bank of Ghana, the cedi has appreciated by more than 42% so far in 2025, a dramatic turnaround after it ranked among the world’s worst-performing currencies in 2022 and 2023.

Today, it sits comfortably among the top-performing emerging market currencies, having regained ground against the US dollar and the euro.

But for many ordinary Ghanaians, the numbers tell only part of the story.

The cedi might look stronger on paper, but its purchasing power hasn’t kept up.

Prices remain high, wages lag behind inflation, and imported goods dominate the market.

For the average household, this means their cedis don’t stretch as far as they used to, regardless of how well the currency performs on global charts.

Voices from the ground

“There have been ups and downs, but under President Mahama’s administration, I think there have been some changes. The cedi is appreciating now, which is good news. I will consider it as a good store of value,” said Michael Oppong, a Forex Exchange trader.

Others remain cautious.

“It has lost its store of value over the years, even though it is doing quite well recently. I still see the dollar as a stronger store of value than the cedi,” Grace Ashong, a market woman at Makola, indicated.

Hajia Rashida Iddrissu, a trader at Abeka Market, reflects on the long-term shift in everyday life:

“Today, most of the money we use comes in higher denominations, but things cost a lot more now. So even though the cedi looks stronger on paper, it doesn’t buy as much as it used to. That’s why the old currency, with smaller notes and more value, felt more useful for everyday spending.”

The expert view: Reforms will tell the real story

Economist Prof. Peter Quartey, Director of ISSER, believes the deeper problem lies in public confidence, which has been worn down by years of high inflation and currency instability.

“The Ghana cedi used to command very high respect some decades ago, while we’ve seen some improvement in its acceptance recently, a currency that faces high depreciation and inflation will always push people to store their wealth in alternative forms,” he said.

According to Prof. Quartey, reversing this trend will require more than temporary appreciation.

Ghana needs to address the root causes of volatility by industrialising, exporting more, reducing import dependence, and ensuring macroeconomic stability.

Looking ahead

At 60, the cedi’s journey mirrors Ghana’s own economic evolution: bold beginnings, tough lessons, and repeated cycles of hope and hardship.

Its recent rebound offers some optimism, but the fundamentals haven’t yet changed enough to guarantee lasting stability.

Whether the cedi can truly serve as a reliable store of value and not just a symbol will depend on whether the country can push through long-delayed reforms.

Until then, the cedi remains a currency with potential, still searching for the full weight of public trust.